58 days after he paddled away from East Wittering Beach into a serene Saturday sunrise, Mike Lambert returned to the same exact point with a “cocktail of very confusing emotions.” He’d been picturing this moment for two months, thinking about how he’d feel. In the moment itself, it was so overwhelming that he felt like he was in a daze.

For 3,020 km around the mainland UK, Mike had endured headwinds, crosswinds, equipment failures, six foot side swell, blisters, some of the most powerful tidal currents in the world, hundred kilometre open sea crossings, sleep deprivation, a chest infection… There were so, so many bad days. And a very small handful of good days. No day was average. The constant extremes and the trauma of those bad days are part of why Mike thinks the memories of his circumnavigation are so clear in his mind.

Even weeks after his return, Mike still remembers every single day of his circumnavigation in detail. “If you asked me today, what have I done every single day since I stopped, I’d have no idea. But with those 58 days, I can recall every single one… although it was only two months, there’s almost three or four years worth of memories.”

I last spoke in depth with Mike when he was stuck in Thurso, at the top of Scotland just west of the Pentland Firth which separates the mainland from the Orkney Islands. He’d had a tough journey up the coast to get to that point, and things didn’t get much easier on the way back down to East Wittering Beach.

Stuck in Thurso: “It was almost like the life went out of me”

The Pentland Firth, the strait that separates the northern/northeasternmost points of the UK from the Orkney Islands, is a notoriously tricky bit of coast to navigate. After weeks of weird weather heading up the west coast, Mike’s bad luck continued in Scotland. Storms and gales blew in from the north and made it unsafe to continue. Fortunately for Mike, he got lucky on land and had a warm place to stay while he was stuck in Thurso. But eight days of waiting on weather took a toll.

Mike’s body had finally adapted to the daily routine of toughing out 50-100 km in conditions ranging from unfavourable to life threatening, wolfing down as much calories as he could find, sleeping on the ground, and doing it again the next day. And the next. And the next… So when Mike stopped in Thurso and couldn’t progress, his body totally lost the plot. “When I stopped, my body felt like it went –” Mike gestured with his hands as we spoke, as if a giant sandcastle was hit by a single wave and immediately crumbled into nothing. “It was almost like the life went out of me.” Just days earlier, his body had gotten him through the worst day of the trip when he crossed from the Isle of Islay to the Isle of Mull in conditions so terrifying that he thought he might not make it. When he got off the water that day, he called his sister and couldn’t say anything, he just cried. But his physical and mental strength had carried him through. Now in Thurso with nothing to do but wait out the storms, his body felt weak, almost frail.

Pentland Firth: swell, stream, and whirlpools

Finally the weather started clearing up. Mike was way behind schedule, so as soon as he could safely make it through the Pentland Firth, it would be Go Time. His body had other plans. After eight days of rest, he started coming down with a chest infection. He felt like absolute crap. But there was no other option – he certainly wasn’t going to quit. On about four hours of sleep, he set out to round the northeast corner of the country.

First up: Dunnet Head. Newfound friends from Thurso stood on the cliffs above to watch Mike paddle through the tidal race. The conditions had calmed enough for him to get around safely, but “calm” was relative. The swell was huge. The waves were so big that the people watching Mike from nearly a hundred metres up couldn’t see him – either he was in the trough of a massive wave, or if he was on a crest then it was so quick he’d disappear from sight immediately. Despite the intimidating conditions, Mike felt confident – after the terrifying day he’d survived paddling from Islay to Mull, today felt completely doable. Through the towering swell, Mike passed the northernmost point of mainland UK and headed toward John O’Groats. This next bit would be exciting.

About 1.5 miles above the northern coast of the mainland lies the island of Stroma. The island is inhabited by only sheep these days, but has a long history. The currents around the island are notoriously powerful and have wrecked many a ship. The island’s name itself, “Stroma”, translates to “the island in the stream” because the sea currents flow around it like a wild river. Mike would be paddling between the island and the mainland.

He headed into the stream. He’d gotten lucky (for once) with a tailwind and spring tide, so the flow was even faster than usual. Even with everything in his favour, it was like paddling a liquid tightrope. On either side of the small channel, he was surrounded by whirlpools. The water comes in at a right angle to the stream – Mike said, “I’ve never been on anything like that before.” But he stuck to the channel carefully, and with the strength of the stream, paddled 5 km in 13 minutes. The fastest 1 km stretch was 2 minutes 26 seconds. The Olympic record in a flatwater kayak is 3 minutes 20 seconds. And Mike was paddling an Epic V8 full of camping gear (on four hours of sleep with a chest infection).

59 km later, he’d rounded John O’Groats, paddled past Sinclair’s Bay, and made it to Wick. When he was stuck in Thurso, he felt like he was never going to get home. Finally getting through the Pentland Firth, his body was suffering, but mentally it was a huge relief. Mike said at the time: “It feels genuinely unbelievable to be through the other end.”

The “easy” east coast

The home stretch. On a map, it looks like a pretty straight shot down the east coast, turn right, a few days on the south coast, and back to East Wittering Beach. Mike had finished Scotland; supporters told him enthusiastically that the worst of it was done, the east coast would be easy. Unfortunately for Mike, the bad luck he’d faced at sea for almost the entire trip wasn’t done with him yet. Both his body and the winds were working against him.

Mike made it through the Pentland Firth, but the chest infection that had started in Thurso was only getting worse. It was hard to paddle, and even harder to sleep. His Garmin watch logged just 46 minutes of rest that night in Wick before Day 36. The infection would persist for almost two weeks. And then there was the wind.

“The east coast is ‘easy’ if you’ve got the prevailing winds,” Mike explained. The prevailing winds are westerlies, offshore winds that don’t have time to generate significant waves since they’re coming over land. Mike got everything but the prevailing winds. He got Southerlies, headwinds that slowed his progress to a painful crawl. He got Northerlies, tailwinds that blew him in the right direction but created huge swell. And even Easterlies, which whipped up big waves and pushed him toward shore.

On Day 52, Mike reached Norfolk and his luck finally turned. He seemed to have finally got rid of the chest infection, and the prevailing wind kicked in. It became one of those rare days – Mike called Weybourne to Hemsby “probably the best paddle of the trip.” At last, he was nearing the finish. Day 53 treated him to a greatly needed tailwind. And that was the end of his luck on the sea…

Final days

Mike was so close, but the weather wouldn’t make it easy. After two days of favourable conditions, he’d now face headwinds all the way home. The headwinds were so bad that it took almost ten hours to cross the Thames Estuary, 69 km from Felixstowe to Kingsgate. He averaged 7.1 km per hour, painfully slow by any measure but particularly after the previous day’s 10.5 km/h getting to Felixstowe. He slogged it out, and committed to an end date and time: the afternoon of 28 July. Back home, Mike’s supporters wondered if he’d make it on time: he had a lot of ground to cover, and would have to ramp up his pace in the face of headwinds.

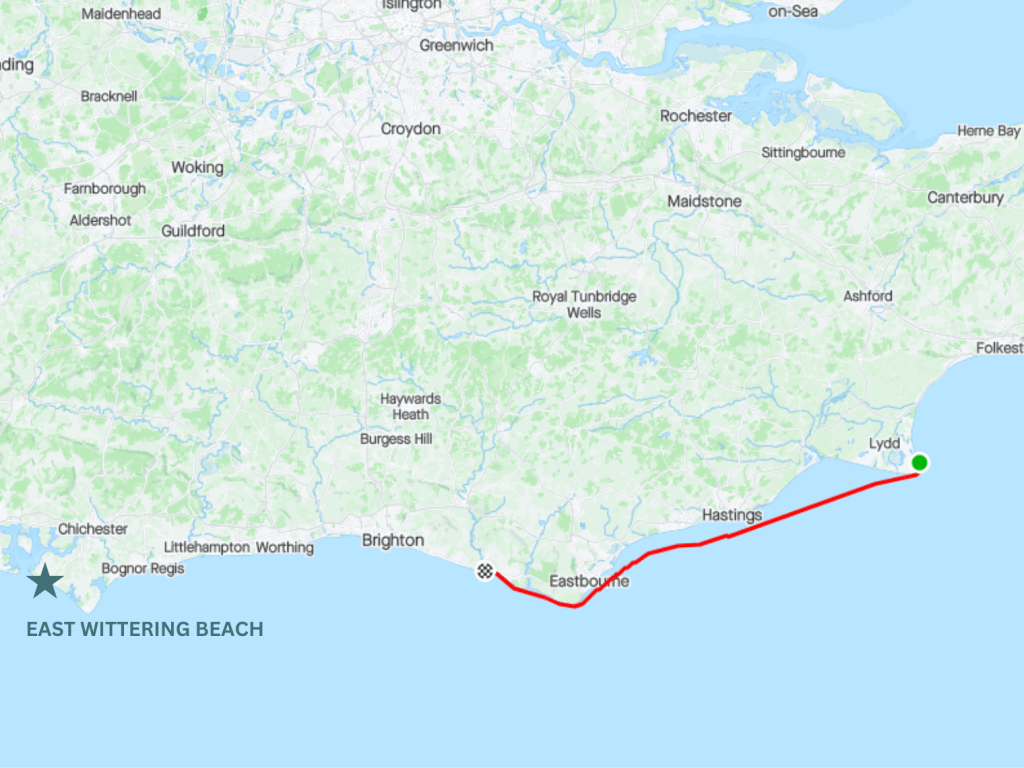

“The second to last day. Oh my god. That was a pest,” Mike recounts. He’d told everyone when he was going to finish, but it meant covering 148 km in two days. On Day 57, he paddled away from Dungeness right into more bad luck: “it was a headwind right down my throat”. The coast opens up between Dungeness and Beachy Head: it’s like a series of small bays that almost form one big bay. Mike had to decide if he would tuck into the coast for a bit of an eddy and shelter from the headwind. But tucking into the coast would add another 6-7 km onto a 76+ km paddle when he needed to reserve energy for his final day. So he decided to go straight across: “I was staring at the headland of Eastbourne for about 9 hours. I thought, I’ve committed to finishing tomorrow, I’ve just got to keep going.” Mike wanted to make it all the way to Brighton, but after rounding Beachy Head, he just couldn’t keep going. He’d been out for almost 12 hours, and now he was on an exposed bit of land with beaches dumping waves. Mike pulled in at Newhaven. 72 km remained.

Day 58. He woke up around 5am after just five or six hours of sleep. Not enough, but it wasn’t the day for a lie-in. It was time to just get on with it. Mike packed up and set off, determined to make the finish on time. He passed Brighton, Shoreham, and Worthing. The sun shone bright, the sea remained calm – it was a perfect day, just like the day he left. And unlike almost every other day of the trip. Just past Worthing, Mike said a brief hello to the leader of his welcome party from the Aortic Dissection Charitable Trust, one of the two charities he’d been fundraising for. He kept on past Littlehampton – just a couple more hours. As he reached Selsey, ready to round the corner for the true home stretch, Mike was joined on the water by paddling friends from home. The cluster of surfskis escorted him for the last 10 km back to East Wittering beach.

East Wittering Beach, 58 days later

Paddlers, paddler families, Mike’s family, Aortic Dissection community members, and supporters of all kinds had gathered on the sloping pebbles to welcome Mike home. He’d built up this moment in his head for so long. It was a huge relief to finally be done. But as happy as he was for it to end, he almost didn’t want it to end. His hands had somehow adjusted to the blisters that come from endless kilometres at sea every day. The journey had helped him manage his grief over the sudden passing of his mother. He’d met so many amazing people through the circumnavigation that he never would have met otherwise. The trip had even introduced a sense of adventure to his life that didn’t appeal to him before.

But for all the positives, there was pain. His back and shoulder were killing him. Mike had dislocated his shoulder a couple years prior and re-injured it just a few months before starting the circumnavigation. Even with all the knowledge that comes with being a physio, he wasn’t able to fix the daily pain from so much paddling. And he’d been out there so much longer than planned. Mike had missed big events; he’d missed seeing his niece and nephew because they’d had to fly out to Brazil the previous week. Going around that last corner, Selsey, and seeing the Spinnaker Tower on the horizon… There were so many emotions. “When you’re actually living that moment, it’s almost too overwhelming to comprehend how you feel.”

On the beach at East Wittering, Mike was surrounded by supporters and showered with champagne. He’d spent the vast majority of the last 58 days alone. But with messages from people online throughout the trip, and help from friends and strangers at each stop, he knew he was deeply supported. In that moment of return, he felt so incredibly loved: “It was a physical manifestation of all that support on the beach. It was like something I’d never experienced before.”

What’s next?

Weeks after finishing the circumnavigation, Mike is still wrestling with its impact on him. In some ways, it almost feels like it was someone else who did it. And the magnitude is hard to comprehend. Mike explained, “It’s not like crossing the Atlantic.” With something like crossing the Atlantic, it’s easy to feel the magnitude. But with the circumnavigation, he was back on and off the land every day, only to finish at the same place he started. He knows that he changed so much during the trip, but during the trip it was still one day at a time: “You live every single second, minute, hour, day of it… it almost feels like there’s no change. Because it’s progressive. And so it’s hard to look back and see any change from before and after. And that’s why it feels like it was someone else.”

Just three days after finishing the circumnavigation, Mike was back to work at his day job as a physio. After the high of East Wittering Beach, going back to ‘normal’ was more than just an adjustment. He acknowledged: “It’s actually very depressing, coming back and living the same life… This huge chapter in your life is closed.” It took about three weeks before he felt recalibrated to normal life. But on a higher level, he’s still processing the effects: “The fact that it was depressing is a byproduct of it being so affirming and life changing. One of the things this trip taught me is that you can’t have one without the other.” Mike is rethinking what he wants to get out of his life. Before he started the trip, Mike said he had no interest in the adventure aspect. It was more about the personal accomplishment, fundraising, and processing grief. Now, he’s realised what a sense of adventure can mean for him. When he was stuck in Thurso, he was struck by a quote on the wall at the bar there: ‘If you live an ordinary life, you’ll only have ordinary stories.’

The stories from Mike’s circumnavigation were far from ordinary. “It’s the stories that come from it being awful, from screwing up… from it being so hard” – those are the rich learning experiences he’s taking away from the trip. And those extraordinary stories are what he’ll be searching for now. Mike says: “There is a way I would like to conduct my life around creating stories and memories.” At the moment, he’s gearing up for the premiere of his documentary, scheduled for next February. And looking ahead to an expedition in Norway next autumn. Until then, he’ll keep processing: “there’s a number of things on this trip – it might even take years to figure out.”

—

Check out my full interview with Mike on YouTube, and subscribe to youtube.com/paddlermedia for more cool stories:

Leave a reply to Heather Garmston Cancel reply