Just before setting off from the Isle of Islay on the west coast of Scotland, Mike looked at the forecast and saw a 20mph tailwind. He thought: “I’m going to have a flippin’ fantastic day today!” More than twenty days into his attempt to circumnavigate the mainland UK, he could count the “good days” on one hand. Mike was overdue for a nice tailwind.

Unfortunately for Mike, his optimism was short-lived. Not only would Islay to Mull fail to be a good day, it would become the worst day of his journey so far.

“Sheer relentlessness”

In training for the circumnavigation, Mike intentionally put himself through brutal sessions. To get enough mileage in, he started commuting to work by kayak. For most paddlers, this sounds absolutely dreamy: forget being packed into a stuffy train car like sardines, instead you’re cruising down the river watching the sun rise and listening to gentle birdsong, enjoying a moment of peace before a busy day of work.

The reality of Mike’s January commutes by surfski was far from dreamy. The alarm would go off just past 4am to allow time for him to pack his drybag with work clothes, paddling clothes, snacks, get down to the river, and launch by 6am. 24km later, he’d battle the rush-hour Uber Boat wakes to pull in at Cadogan Pier just in time for sunrise. It was still two more kilometres walking along the pier, surfski on the shoulder, dodging commuters wearing full make-up, heels, and designer bags. Past 7pm, he was back on the water again, now fighting against the tide for another 3 hours commute home, shaking icicles off his drybag upon arrival.

But as brutal as those days were, Mike says: “It’s completely blown out of the water by the sheer relentlessness of what a trip like this looks like. You could do a 100km paddle as a one-off, and once you’ve got through that, you’re done. Here, once you’ve done a 100km paddle, you’ve got at least another 30+ 100km paddles still to do. And with the weather conditions… the same effort you did to get you those 100km might only get you 60km today, or 40km tomorrow.”

The worst day

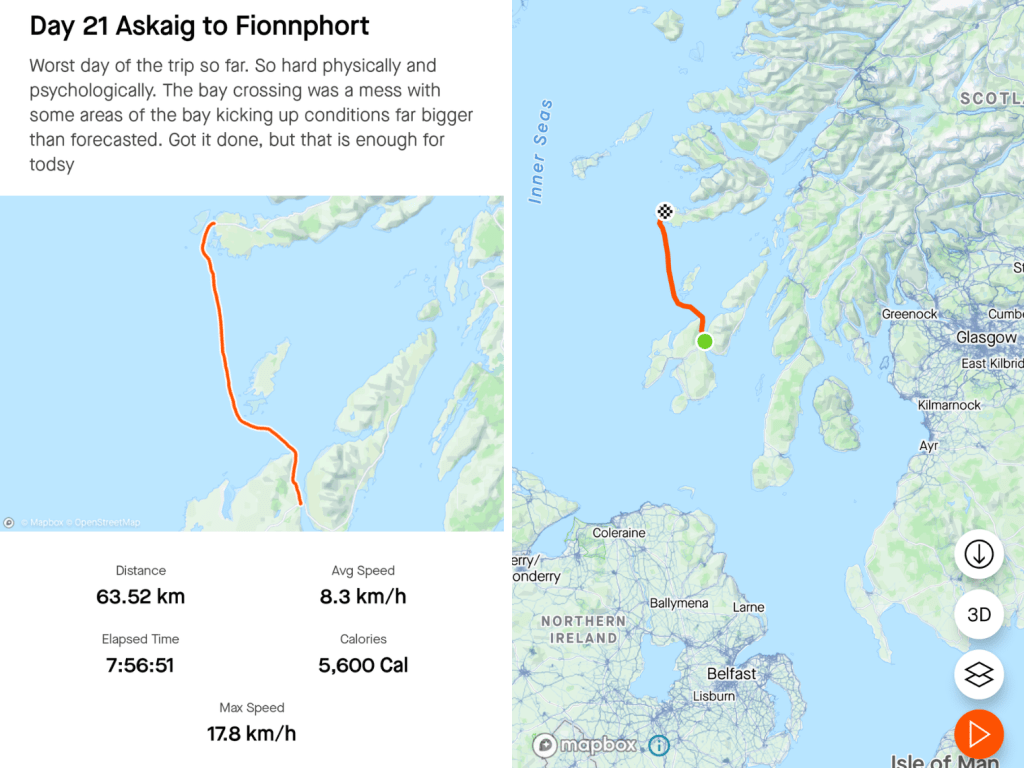

On 21 June when Mike set off from the Isle of Islay, the UK was experiencing one of the coldest Junes on record: Scotland’s Cairngorm Mountains even saw a dusting of snow. Out in the Atlantic, a storm was raging. Far enough to be safe for Mike to depart Islay, but close enough to make waves. The ocean swell rose to 6-8 feet, thrashing Mike’s ski from the side. And then there was the tide. Thanks to some questionable local advice and decision-making on Mike’s part, he missed the tide window. Instead of getting a nice push toward Mull, he was getting sucked backwards toward Northern Ireland.

Mike tried to forge ahead through sheets of rain, searching for clear water amidst the reefs and low lying islands that pepper the sea between Islay and Mull. One big wave could sweep his surfski onto the rocks lurking beneath the swell and leave him stranded.

Five hours later, Mike could just make out his destination in the distance. “I didn’t think I would need the Coast Guard, but I did think that if I didn’t get in soon, I’m gonna really, really be in a mess.” Three more hours and he made landfall. Sixty kilometres total. On paper, it looked underwhelming. Mike wondered if he would be able to get back on the water.

Finding the limits of resilience

Mike started the circumnavigation motivated by grief and resilience. But the motivation that got him to the start line isn’t enough to get him back on the water each day. “Doing this, I have never felt weaker in my whole life. It has broken me right down into the smallest little piece that I could possibly be. When we think about what it feels like to feel resilient, that’s not how I feel – I feel weak, pathetic, I don’t feel strong at all.” The hard line that’s keeping him going now is fear of regret.

After the worst days, when he doesn’t want to get back on the water, Mike reminds himself: “If I were to quit now, in about twelve hours sitting on that comfy sofa, I’d think ‘what the hell have I done.’ To quit now because I’m sad, or because I’m tired – I just think that would be the most pathetic excuse, because I’ve been through it all now.”

Cape Wrath

Even after making it through the Islay to Mull crossing, he feared the worst was yet to come: Cape Wrath. Supposedly, the name comes from Old Norse for “turning point,” but conditions can get scary enough that “wrath” feels accurate. Fear of rounding Cape Wrath had loomed large in Mike’s imagination all the way up the West Coast. He built it up so much in his head: the size and direction of the waves, if he’d be tossed out of the ski and thrown against the cliffs, how much more pain he’d have to manage. Standing on the beach before setting off for Cape Wrath, the emotions were overwhelming. Mike cried. As he wiped away the tears and steeled himself for the worst, a runner came up to ask for a photo – Mike grinned. After all that, Cape Wrath turned out to be fine. Conditions were relatively calm and he mostly sailed through smoothly. The last portion of the paddle was brutal. But nothing he couldn’t handle.

Managing expectations throughout the journey has been a doozy: “There have been elements of this that have been worse in imagination than reality, and there have been many other bits that I thought would be fine and have been terrible.” Constantly having to adapt to the unexpected is changing Mike off the water too. Reaching the north coast of Scotland, Mike started to recognise new habits and traits.

“Committing myself to a journey like this has forced me to develop aspects of my character that would have been completely neglected.” As much as he’s found that fear of regret is his ‘hard line’ motivation, negative self-talk doesn’t get him very far on the water. Back on the South Coast, Mike was letting the frustration get to him, calling himself names. He recognised that wasn’t helpful, but knew that blind positivity wouldn’t help either. In a major paddle through conditions that require the utmost levels of preparedness and awareness every day, taking a platitude like “oh you’ll be fine, just go smash it” at face value can be dangerous.

Since the South Coast, he’s shifted his mindset. Instead of wishing for things to be easier, he wishes that he was stronger. When approaching a massive crossing or difficult weather conditions, Mike starts with the evidence: “What am I facing? It’s a bay crossing? You know how to do bay crossings. What if something goes wrong? Mike, you know what to do if things go wrong. You’ve been in tough situations before, you’ll make it through this one.” More than just a mindset shift, Mike feels a shift in himself that he’ll take to all aspects of his life: “Once you know that you can do something, that task loses a certain degree of its power over you.”

More than mid-way through his circumnavigation of the mainland UK, Mike is making peace with the unexpected. He knew before he started that this would be the most demanding thing he’s ever done, and that’s what he trained for, both mentally and physically. Even so, the challenge has been bigger than what he anticipated: “The hardship that I’ve endured, in particular the weather hampering my progress, has forced me to fundamentally change my approach. I feel changed as a person because of what I’ve had to endure.”

Learning to put down the pain

The idea to do the circumnavigation came to Mike in December 2022 after his mother passed away suddenly from aortic dissection. He’s been open that part of his goal was not just raising awareness and money, but also processing his personal grief. Now, he acknowledges that it wasn’t just processing the grief but almost justifying it. “What I felt I needed to do was almost legitimise my grief and the horrendous experience I had. No one should ever have to feel like that. But for one reason or another, that’s how I felt. And it wasn’t something that I could talk myself out of.”

Reaching the North coast, Mike started to realise that he could put down the pain: the pain from each day’s paddle, and the pain of how he lost his mother. “Every time I get off the water, I don’t need to relive that chapter of pain again. Because when I get off, it’s done, it’s finished. I don’t have to do that bit again, I don’t have to experience that again.” Before this point in the circumnavigation, Mike says he felt like he was holding onto the pain. Now, he realises there’s very little value in picking up that pain and feeling it again. It serves a purpose in reminding you not to make the same mistakes, and that’s enough. Wrapping his mind around this aspect of the paddling has been a “visceral learning experience.” Mike says: “Losing Mum in the manner I did was so unbelievably painful, but actually realising that there are certain elements of the pain that I felt around that that I’m allowed to put down has been huge.”

He’s not letting go of his mother, or even really ‘moving on’ from the grief. But he’s starting to understand the destructive potential of sitting in his grief for too long. He has to put down some of that pain in order to move through the next day, on the water or otherwise.

Mike is on the “home stretch” now paddling down the East Coast back towards his starting point at East Wittering. He won’t beat Dougal Glaisher’s 40 day record from 2023, but he’s aiming to finish before the end of July- recent illness since Thurso has put up yet another roadblock, but with the help of antibiotics, Mike is pushing through. Follow his progress at livelaughgraft.com/track-me, @livelaughgraft on Instagram, and here with us at Paddle Daily on the website, Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube.

Check out the full interview on the Paddler Media YouTube channel:

Leave a reply to Heather Garmston Cancel reply