2024 brought some of the highest highs and lowest lows for Britain’s international sprint kayak racing programme. The high: it was Team GB’s most successful Paralympics ever with a record 8 medals. The low: for the first time ever, no GB athlete qualified to race canoe sprint at the Olympics.

So in January 2025, Paddle UK brought on Ekaitz Saies. Ekaitz raced internationally for Spain for 15 years, won world titles in 2009 and 2011, earned a PhD in Sport Psychology, and coached Spanish Olympic athletes to unprecedented success before moving to the UK. In August, he officially stepped into his new role as Paddle UK Performance Director for Paracanoe and Canoe Sprint.

In other words: he’s the person in charge of making sure GB is well represented in Los Angeles.

That goal places a lot of pressure on Ekaitz. But he’s ready for the challenge: drawing on his background in sport psychology, Ekaitz’s first step is believing that the goal is achievable.

The road to LA 2028 starts with “Believe”

Speaking to Betsy and Billy on Paddlecast, Ekaitz said that one of the first things he noticed moving from Spain to the UK was the culture: “I didn’t feel there was a healthy environment to really strive for excellence.” Within the performance squad, he’s been working to re-build the confidence of a team still scarred from 2024: “Not qualifying for Paris was a big blow for these athletes. And I could see that they lacked the confidence to really perform their best.”

As Ekaitz explains the crucial role of sport psychology in athletic performance, he sounds more and more like Ted Lasso. Step 1 is that you have to believe that you can win. And he’s the first one to put that into practice, saying: “I strongly believe that we have the best women’s squad this country has ever had.”

The bar to beat is high: at the London 2012 Olympics, the K4 of Jess Walker, Rachel Cawthorn Schofield, Angela Hannah, and Louisa Sawers finished in 5th place. Rachel and Jess performed well in the K1 events too, reaching 6th and 7th place in the 500m and 200m events, respectively. It was the best Olympics GB women have ever had: although Team GB collected an impressive 9 medals in canoe sprint from 2000 – 2020, all were in the men’s races.

Even considering those strong results in London, Ekaitz thinks the current team is better: “I do believe that the current cohort has the qualities and the potential to do even better than that.” Better than 5th place is tantalisingly close to medal territory. If Ekaitz is right, we may well see the first ever Olympic medal awarded to GB women in LA.

Team GB is betting big on the current six-woman squad of Olympians Deborah Kerr and Emily Lewis (Tokyo 2020), U23 European Champions Kristina Armstrong and Zoe Clark (Bratislava 2025), Emma Russell, and Lucy Lee-Smith. They might just have the magic that makes a crew boat more than the sum of its parts. Ekaitz describes the feeling: “When you see them interact, you’ll see it. You sense it. You enter the room and you sense that there’s something special between them and how they talk to each other, how they behave.”

Ekaitz says that in his years working with the Spanish team, it was the single-minded belief in a shared vision that allowed them to break a 40+ year medal drought in K4: “The vision was to win a medal, and everything that we designed or the training plans and the psychological aspects were just to make sure that we would achieve those goals.” At Tokyo 2020, Spain took their first K4 medal since 1976: silver for Saúl Craviotto, Marcus Cooper, Carlos Arévalo, and Rodrigo Germade. The same team stayed together and took bronze in Paris. Once they earned that first medal, they knew they could medal again.

“Believe” is the foundation of Ekaitz’s strategy for the performance squad, but he’s also noticed more institutional opportunities to improve sprint canoe in the UK based on differences in paddling culture compared to Spain. Please note that Ekaitz’s willingness to share his thoughts openly on Paddlecast did come with the caveat that the views expressed are entirely his own and represent his personal perceptions.

From Spanish paddling culture to British paddling culture

The differences sound mundane: calendars, race distances, technical nuances, even the number of paddlers in a group together during training sessions. But these differences have far-reaching consequences.

The first example Ekaitz cites is calendars: “When I worked in Spain for nearly a decade, the process of creating a racing calendar was very, very simple and streamlined.” Just three people – the Performance Director (Ekaitz), the Head of Pathways, and the Head of Competition – created a single, national calendar for all disciplines from sprint to slalom to dragon boat. Their approach assumed that paddlers might want to take part in both marathon and sprint, or sprint and downriver racing, and allowed for that in the schedule.

In contrast, the UK has different committees for different disciplines (e.g., the Sprint Racing Committee versus the Marathon Racing Committee), and Ekaitz says “each committee has their own agenda and vision about how the calendar should be distributed.” The added complexity in the UK makes it more difficult to manage clashes across disciplines.

Where the UK offers racing virtually every weekend, particularly in the marathon discipline via the Hasler Series, the volume of races in Spain is lower and includes more events in the “mid” range of distance. The first race of the year is a 5 km event in March where both the sprint and marathon paddlers compete. With around 1000 entries, it’s the biggest national event of the year (not counting the Sella Descent, Spain’s premier international race).

As much as schedule and distance matter, there’s also technique. Ekaitz says that the top Spanish clubs “tend to be very clear on sprint technique [versus] marathon technique that I didn’t find the same context in the UK in some of the clubs.” Physiologically, aspects of “good” technique in sprint racing can destroy your body over marathon distances – for example, having higher arms gives a sprinter more leverage and power, but could put a marathoner at risk of injury over 30 km. The best multi-disciplinary paddlers understand these differences in technique intimately, and adapt their style accordingly. Ekaitz describes Fernando Pimenta as this kind of “Swiss knife” paddler, someone who can adapt his technique depending on the event.

Even a simple change like having smaller groups at club training sessions can enable marathon paddlers to practice sprint technique. Ekaitz describes an ideal option as formations of four paddlers changing wash leads every four minutes, where the lead paddler is using sprint technique. Because they only have to sustain it for four minutes, the risk of injury drops, speed increases, and technique improves. That’s the type of habitual, micro-level change he’s been discussing with coaches who want their paddlers to improve at sprinting.

What to look for from canoe sprint in 2026

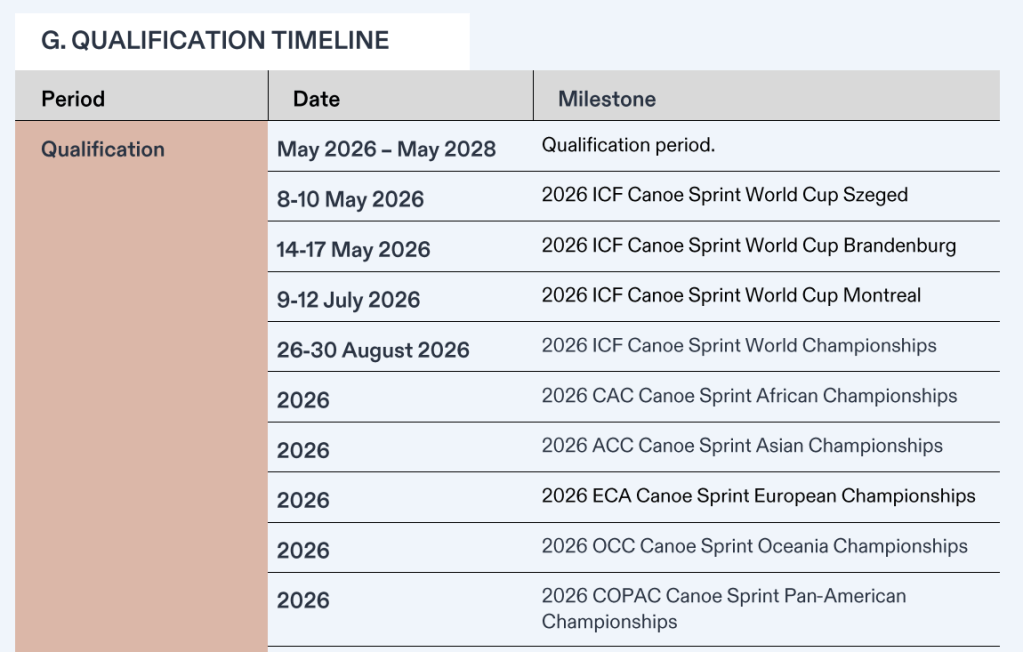

The Olympic Qualification period officially begins in May 2026, and the system is changing to be based on the ICF’s World Rankings rolled out last year. This makes the World Cups more important, and should result in a higher level of competition at World Cups. The ICF has also added a third World Cup, outside Europe, hosted in Canada this year.

For Team GB, the change means moving to a periodised approach with multiple peaks to align with the three World Cups and the World Championships. Unlike previous years where World Cups felt lower stakes, the team will feel more pressure to perform earlier in the season. That said, World Championships are still the most important: those results are worth 1.5x qualifying points compared to World Cups.

For some less well-funded teams or teams with longer flights needed to travel to Europe/Canada, the higher costs might mean bringing a smaller squad of only the top athletes. The level of competition at the World Cups will be higher, but participation rates may be lower. Subscribe to Paddle Daily to follow how these changes end up affecting canoe sprint in 2026.

Listen to the full Paddlecast episode with Ekaitz on YouTube, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts. And follow Paddle Daily via this website, Facebook, or Instagram.

Leave a comment