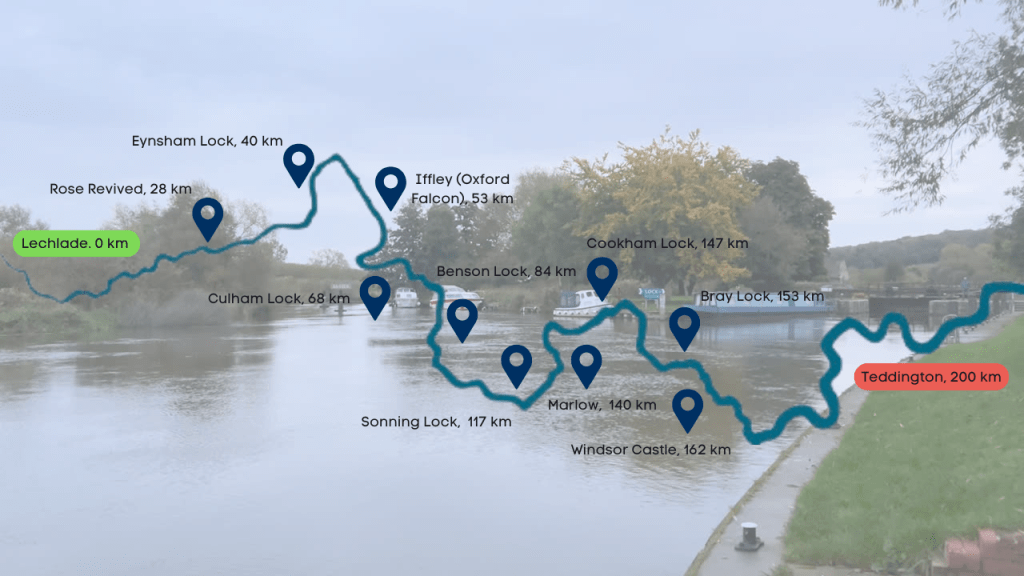

3:30 am: Lechlade on Thames

The headlights on the van shone brightly on empty pub tables. Past the tables, the river looked like a black mirror. It was only once you walked right up to the side of the river that you could see how fast the water was racing. In the back of the van filled with kit, Billy Butler poured electrolytes into a bottle and shook it up. If everything went to plan, he had at least 16 hours of paddling ahead.

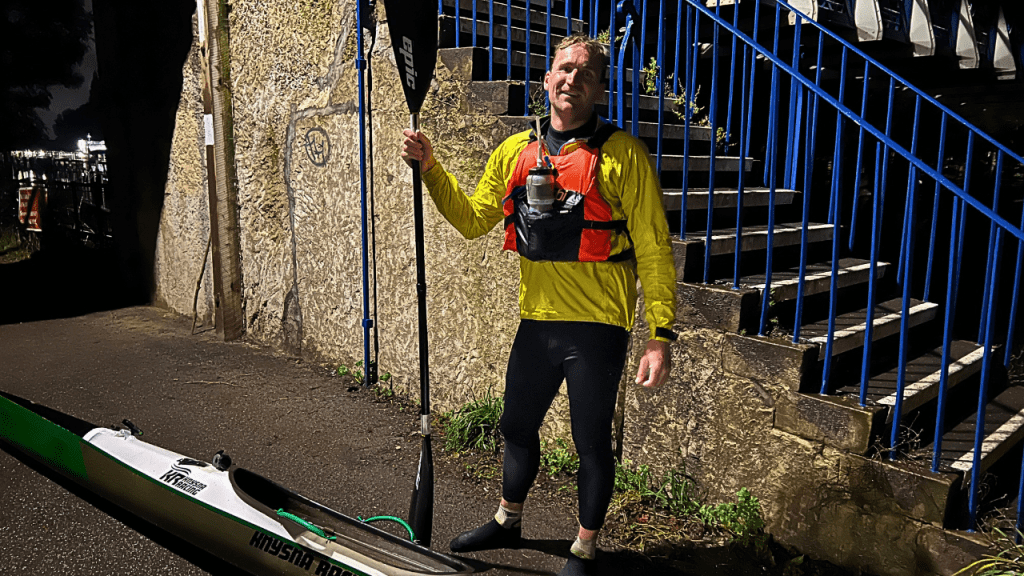

Billy likes kayaking records

Billy likes records. “I’m not addicted to it. Or am I addicted to it? I don’t know,” Billy pondered the night before setting out for another record. His attempt to set a new solo kayak record down the 200 km length of the Thames wouldn’t even be his first record attempt on the Thames this year. In April, he and Tom Dawson broke the doubles record for the length of the Thames in K2: they cut nearly five hours off the previous time set by Steve Backshall and Tom McGibbon, finishing the full length of the navigable non-Tidal Thames River in 15 hours and 44 minutes. Just two weeks before this Thames solo attempt, Billy was in his surfski to set a new record for the fastest circumnavigation of Anglesey: 9 hours, 18 minutes. He also holds the current record for fastest circumnavigation of the Isle of Wight from 2023: 6 hours and 28 minutes. He held the doubles record for Hayling Island until Tom Holland and Alex Sheppy snapped it up earlier this year; so he returned with Andrew Birkett and took the record back again.

I asked Billy how he was feeling. “Quite casual”, he answered. For someone about to paddle as fast as he could for 16 hours down a river moving at near-perilous levels of flow, he seemed very relaxed. But after breaking four records in a year, this moment was nothing new. Billy sounded ready: “I know I’ve got it in me. I’m well prepared.”

As confident and relaxed as he seemed sitting on his sofa with his van jam-packed with kit for the next morning, Billy still had doubts: “It’s a big question mark for me whether I can get all the way on my own without the backup of the second paddler.” The river levels were similarly high as when he broke the K2 record with Tom Dawson but now he’d be facing the swirlies solo. An experienced second paddler not only adds stability and speed to the boat physically, but also brings motivation and improved decision making. Paddling 200 kilometres solo would require the ability to remain upright in an unstable boat after 16 hours of hard paddling, plus exceptional focus and perseverance. It looked like Billy had the right ingredients, but taking the record wouldn’t be easy.

Nearly 4:00 am. Start in the dark

In Lechlade, Billy checked the lights on his boat and he was ready to go. The clock was ticking, nearly 4am. As he pushed off the bank toward Ha’penny Bridge, the official start of the navigable Thames, his support crew for the day left him with some simple advice: “We know that you can do this shit, so just get on with it.” Nick Kay has been supporting Billy for over a decade. He knows precisely what he’s doing.

At 4am on the dot, Billy cautiously paddled into the dark beneath Ha’penny Bridge with about as much current as you can get near the river’s source. The plan: keep it casual off the start. In Billy’s words, “If there’s going to be any heroics, it’ll be in the daylight.”

6:18am. Still dark.

Two hours and 28 kilometres later, Nick and I found Billy at the Rose Revived pub. As Nick called out to bring Billy into the bank, he responded: “You might be surprised, but you’re the only torch out here.” Billy’s sense of humour was intact. His main torch light was not. Since he’d set off at 4 o’clock, the thick layer of low clouds hadn’t budged. Nautical twilight, that hint of grey-blue along the horizon foreshadowing the fast advance of daylight, should have started at 05:58. Instead, it was pitch black. Without the light from his main torch, Billy was navigating using his tiny backup torch and pure instinct. The fast-moving flow would help keep him in the centre of the river… until it wouldn’t. With twisty riverbends, overhanging trees, and floating debris, the current could just as easily send Billy into an unseen obstacle and end his record attempt in an instant. Luckily his instincts seemed to be sufficient, and dawn would arrive soon enough (even if it didn’t look that way), so Nick removed the broken torch and sent Billy off to the next stop.

7:14am. Day(light).

By Eynsham Lock, day had finally arrived. “Day” as in, it was clearly daytime, but the “light” part of daylight arrived so mutedly that there was no recogniseable sunrise. For Billy though, all that mattered was being able to see clearly again. He powered into the lock portage looking like the river’s improved visibility had given him a speed boost since he abandoned his broken torch at Rose Revived. “You want to slow down a bit!” shouted Nick. Billy jogged past with his kayak and flashed a grin at the camera. He looked strong in the boat, spirits were high, and he was on record pace. But he was only three hours in – could he keep up the same energy all the way to Teddington Lock?

On the other side of the lock, Billy paddled sideways, angling his boat into the bubbling weir stream. The fast flow was on his side. He would need it as his energy began to wane.

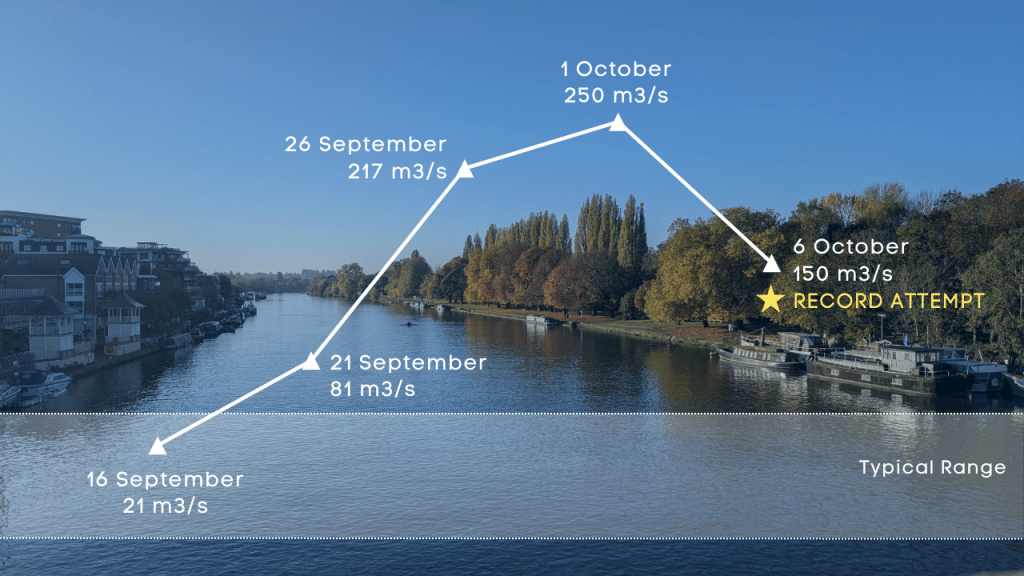

The perfect conditions

Breaking a record is very different from paddling a race (except, of course, for when you’re breaking a record during a race). A record requires perfect or near-perfect conditions: for the non-tidal river, fast flow downstream but not so fast as to be overly treacherous. For the sea, a powerful tide in the right direction and/or a weak tide in the wrong direction. Tailwinds, daylight, and decent temperatures if at all possible. And of course, you need a paddler who has all the skills to handle the conditions, who’s fit enough to maintain a top speed, equipment that will hold up and keep the paddler comfortable, preferably an experienced support crew… All that has to be ready to go as soon as the conditions are right, which is sometimes on just a few days or hours notice. Billy enjoys the records so much that he’s gotten into the habit of checking every week: “Every week, I’ll go: what’s the tide doing? Is it spring tide, is it neap tide? Is it raining, where is it raining in the country? Does it mean we can go down the River Wye, the River Avon, the Exe… If it’s spring tide, where is there a high pressure system, because could anyone go around Hayling Island? Or if it’s a neap tide, is there a possibility of an Irish Sea crossing?” Billy summarised: “If you don’t look, then it’ll pass you by.”

He chose the date for his Thames solo attempt carefully. After days on end of heavy rain – exceptionally heavy rain for the south of the UK in September – the river was flowing fast. At the end of the non-tidal Thames, in Kingston, the flow rate jumped from 26 cubic metres per second to 224 in just two days. The flow would be equally quick or even faster over the winter months, but then it would be cold and dark. If the current was moving too fast, especially in the cold and dark, 10+ hours of paddling solo could very quickly turn dangerous.

Billy picked his craft as carefully as he had the date for the record attempt. He’d have to paddle fast to get the record time he wanted, but paddling his typical flatwater racing kayak could exhaust his core stability long before 16 hours. Speed wouldn’t mean anything if he couldn’t finish the distance. The craft would have to be a balance between speed and stability. Billy decided to take his Knysa descent boat, built and customised for going down rapids and over weirs. The design would be fast enough to keep him moving quickly, but with a bit more stability than his racing boat. He started off with a low seat too, just in case – sitting right down into the bottom of the boat, he’d be at maximum stability speeding around the tight corners of the upper Thames in the dark.

8:13 am. Oxford.

“I’m feeling pretty good. Can’t complain too much,” Billy said as he pulled into the familiar pontoon of the Falcon Boat Club in Oxford. The river was already teeming with rowers for whom 8 am on the Thames was a typical Sunday. It was a far cry from the countryside silence in the earlier hours of the morning upstream. “The light issue was really bad, and the speed really suffered with losing the torch. But the speed has picked up again.” Monitoring his speed closely against his goal pace, Billy was reassured that one equipment failure, frustrating as it was, wouldn’t be enough to end his record attempt today. Feeling stable enough to swap to a higher seat, he hopped back into the boat and waved at the camera as he pushed off toward the downstream bridge decorated end to end in rowing team graffiti. Oxford marks the end of the Thames River’s detour north before it turns back to run south east towards London. Still over 130 kilometres remaining.

10:36 am. Benson lock.

Tom Dawson, Billy’s partner during the doubles record on the Thames last April, fought upstream against the current in his K1 looking for Billy. Tom had thought about going after the solo record as well, but ended up not being able to make the logistics work. Joining Billy for a few minutes on the water would be the next best thing. Billy had been on the water for six and a half hours at this point, and despite his pep earlier in the day, it was clear he was starting to feel the mileage. He swapped over to use a paddle with slightly smaller blades – like downshifting your gears on a bicycle in Nick Kay’s words – and drank a much-needed Coke.

From here, the river would widen and start to look more like the familiar Devizes to Westminster race course which the Thames meets in Reading. For Billy, that would be about his halfway point.

Noon(ish). Halfway.

Billy kept jogging through the portages at Goring Lock (11:33am), Pangbourne, Mapledurham, and Caversham. The fastest known solo kayak time from Lechlade to Teddington was 20:56:52 set by Richard Buston during the Thames 200 Ultra in August. As long as Billy could make it all the way to Teddington, he had enough of an advantage from the fast-flowing river that he would almost certainly beat that time. But to properly break the record and set something respectable for the fast conditions, Billy wanted to get as close to 16 hours as possible. Ideally, he’d reach Reading and the halfway point at 12:40 pm. He made it through Reading, but the 16 hour mark was slipping away. At this stage, he was starting to get more concerned with just getting to the finish.

Billy paddled into the Sonning lock cut at 1:17 pm. Mountains of water gushed over the weir to his left, but the noise faded behind tall golden trees. Still water reflected delicate branches and leaves just starting to indicate the changing season. The clouds that buffered sunrise earlier in the day remained low in the sky, refusing to let light through. At least it wasn’t raining like the forecast had predicted.

He still looked solid in the boat, but Billy was not feeling great. Sonning marked 116.8 kilometres and more than 9 hours of paddling. The pain had pretty well set in, and he still had at least seven hours left. He kept paddling.

4:02 pm. Marlow.

Sometimes near the beginning of an ultra distance paddle, things can go from bad to better. Even after a few hours of paddling, you might find yourself settling into a rhythm and feeling stronger than you did at the start. Or conditions get easier because the current picks up or the headwind slows. Or you take your first dose of painkillers and start to feel like you could keep going forever.

But once you’ve passed the halfway point, especially when that point is 9 hours in, things rarely get better. Caffeine, sugar, pain meds, faster conditions – you’ve been there done that. Your body and mind are over it. Whatever mental or physical tricks you try to throw at yourself become brief distractions from pulsing pain and monotony.

For Billy, the hours and mileage were ticking by as hundreds of cubic metres per second of water pushed him down the river towards London. But he was hurting. Billy confessed: “I’m not feeling very good.” It was exactly the parts of doing this solo that he knew would be so much more brutal than when he’d broken the record in K2. “I am sore. I’m tired. Mostly my back, my shoulder, and my stomach are very sore.”

Billy’s support person, Nick Kay, reminded him that however much he was hurting now, he’s had doubles partners in ultra distance races who stuck it out with him through worse. If Billy’s paddling partners could push through that for Billy, then Billy could push through his own pain solo. He wasn’t ready to give up yet.

“On we go.” Billy pushed off from Marlow lock. 59.5 kilometres left.

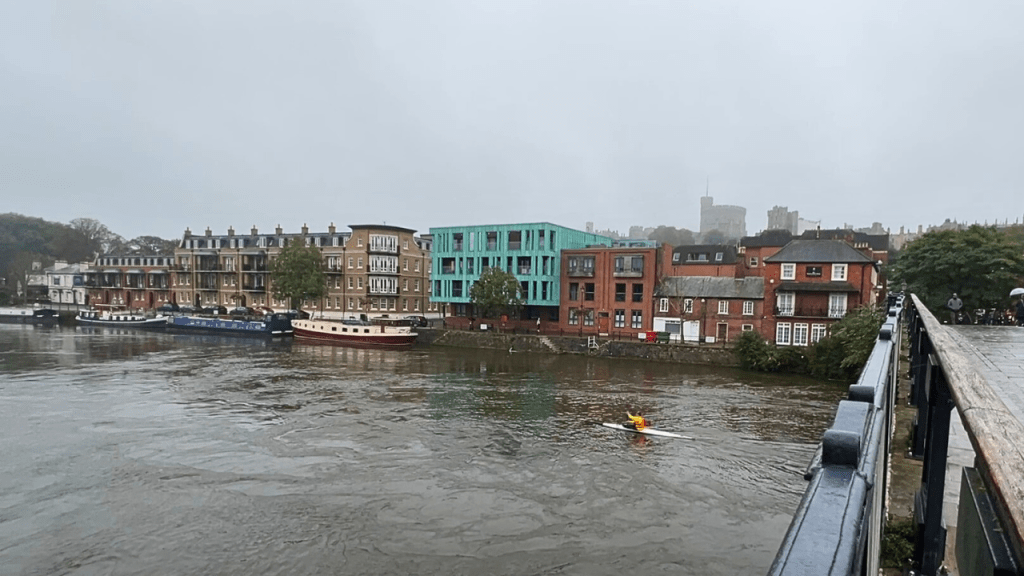

5:08 pm. Windsor.

The forecasted rain finally arrived: a gentle drizzle from low clouds that dropped even lower to bring rain. Windsor Castle loomed large above the river, a dark grey outline against the light grey sky. Seagull calls cut through the dampened Sunday bustle of a rainy afternoon.

Billy’s neon yellow top emerged from the mist. Watching from afar, he was moving well down the centre of the stream. Looking up close, his strokes were a bit halting: the pain showed through. He cautiously manoeuvred through the strong current toward the next lock and support point. At least with the current in this section, he was picking up speed on the water.

Sunset would arrive soon with the same fanfare as the day’s sunrise: whispers, at most. At least Billy’s broken torch from the early morning start was fixed and ready to take him through the remaining hours of darkness.

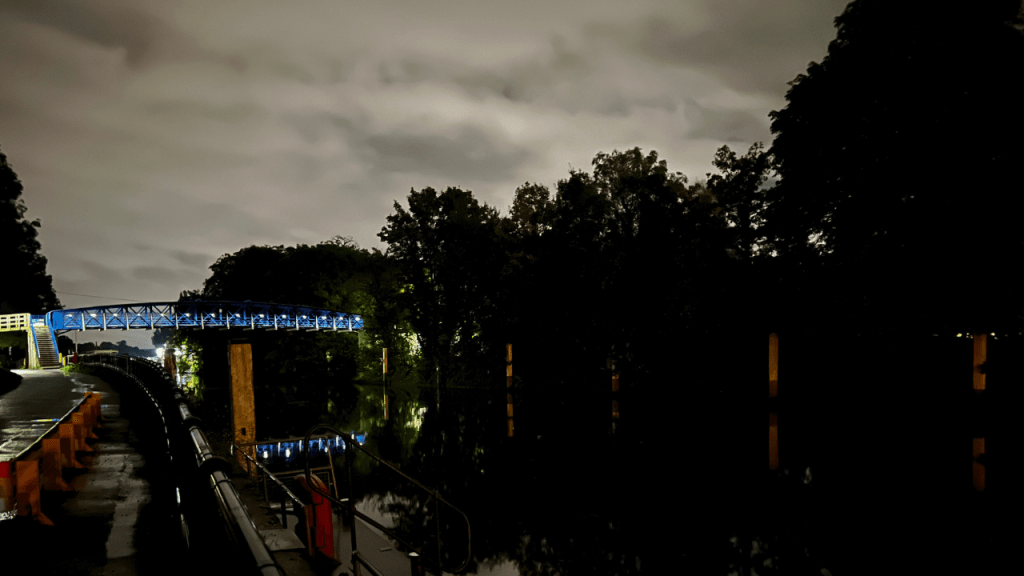

8:31 pm. Teddington.

There was hardly a soul in sight at Teddington Lock after the day’s unending grey punctuated only by drizzle. Billy’s GPS tracker inched slowly closer down the final stretch of the non-tidal Thames. The little lights on the blue footbridge reflected on dead still water.

At last, the bow of Billy’s kayak, pushing a bundle of leaves no longer worth trying to bounce off, rippled through reflection. All the way to the lock – he slowly paddled toward the official end point. Done. 8:31 pm. He’d broken the record by more than four hours. 16 hours, 31 minutes.

Farewell, Thames

The solo Thames record was one of the last stops on Billy’s self-described “farewell tour.” In just a few weeks, he would be moving to the Netherlands. Branding his name on some of the most prestigious records in the UK meant all the more knowing that defending those records will get a lot harder from his new home across the North Sea. He’s not done chasing long records and crazy paddling adventures though. Two weeks after his Thames record, Billy returned to Hayling Island with Andrew Birkett to take the doubles record back from Tom Holland and Alex Sheppy. At some point after he’s settled in the Netherlands, he wants to paddle back to the UK. For now, that record belongs to Belgian sea kayaker Dimitri Vandepoele.

Until then, Billy has made peace with the possibility of losing his many UK-based records to ambitious paddlers. If they can beat his times, that is. Standing on dry land again at Teddington Lock after more than 17 hours awake with a long drive home, Billy felt satisfied with his new record: “One of the big things was I just didn’t know whether I could do 200 km on my own. And I can. So I’m quite pleased with that. Someone else will come and do it, others have done it before. So until someone goes down a bit quicker, I’ll enjoy it.”

Leave a comment