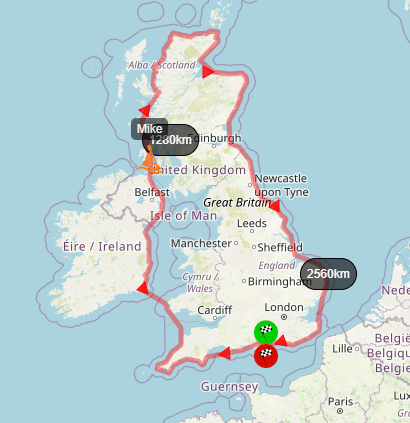

On 1 June 2024, Mike Lambert set off on his attempt to circumnavigate the mainland UK by kayak. Not just aiming to complete the circumnavigation, a phenomenal 3,000+ kilometre feat in itself, Mike’s goal is to set a new record of finishing in less than 40 days.

An unlikely candidate

Although Mike raced in elite sprint kayak as a junior and on Team GB’s U23 team, he wouldn’t strike you as a likely candidate for such an ambitious athletic feat. When he started training for the circumnavigation in December 2022, his self-described fitness was “96 kilos of hibernation physique”. Work and academics had taken a toll while he was training to be a physio to the extent that climbing the stairs had become an aerobic workout. But even back when Mike was in top form racing international regattas, his paddling mates called him “the only sprint paddler who could blow out before the end of a 200 metre race.” The challenge wouldn’t be just regaining the fitness of his youth, but building a new endurance base ten times better than he’d ever had before. Why take on something that seemed impossible?

Everything in Mike’s life had changed when his mother died suddenly of aortic dissection in November 2022. Caroline Lambert was his champion. On top of working long hours as a District Nurse and raising Mike and his sisters as a single parent, Caroline spent hours frequently driving Mike around to regattas. When finances were tight, she made sure Mike had what he needed to pursue competitive kayaking. Mike says: “I never heard the words ‘you can’t’ only ‘how can we achieve it’. Without this attitude, I wouldn’t be where I am today.”

Mike remained very close with his mother as he grew up and trained to be a physiotherapist, a career inspired by Caroline’s career in nursing and passion for helping people. Her sudden passing hit him hard, not just because it was unexpected but also because of the way it happened.

Caroline Lambert

Note – Mike’s experience with his mother’s aortic dissection is difficult to read, and may be triggering if you’ve had traumatic experiences in a hospital setting. Sharing his experience to raise awareness of aortic dissection is why Mike has taken on this circumnavigation, but if you prefer to skip ahead, scroll down to the section “The Art of Resilience”.

Caroline had gone to the hospital with neurological symptoms including hand weakness, but the doctors didn’t have a diagnosis for her. Mike’s grandmother had gone through something similar, been diagnosed with aortic dissection, had the surgery, and survived. So Mike and his family were well aware that they had a family history of aortic dissection and informed the doctors – they feared that Caroline was going through the same thing as her mother had, and hoped for the best.

The doctors had done an echocardiogram (ECG) to determine there was no arrhythmia and she wasn’t having a heart attack, and Caroline’s symptoms were improving. “We told them that we have a family history of aortic dissection, and that’s what’s going on.” Not only had Mike and his sisters been through this with their grandmother, but Mike had the foundations of medical training from his experience as a physiotherapist and knew he was right to be concerned.

But when he got there: “The working diagnosis was nothing. They said ‘No, no, your mum’s fine. We don’t think it’s a heart attack, we don’t know what it is, but we think she’s okay.’” Caroline was left in General Admissions with just one nurse for every six beds.

As Mike stood by his mother, he suddenly realised she was having a stroke: “My background is physical therapy; we do neurological assessments. And I think even to the layman, you can recognise someone’s having a stroke.” He immediately went to find a doctor. But the hospital staff failed to recognise the urgency of the situation. It took them nearly 45 minutes to get to Caroline.

When the doctor finally arrived to do the assessment, they weren’t confident in what was happening and went to go get someone else. Then they went to get the stroke team.

As every clinician came over to his mother’s bedside, Mike and his family told them about their family history with aortic dissection. But she still had no diagnosis. The seconds and minutes passed painfully, growing into an unconscionable delay. Mike explains what was happening in his mother’s heart: “With the aortic dissection, there’s a tear in the innermost lining of the aorta and your body tries to repair that. But basically the pain of that made her physically sick, and then the pressure generated by her being sick threw off the clot and she had a stroke.”

Finally, one registrar checked and found a huge aortic dissection. The doctors couldn’t treat the stroke without treating the aortic dissection because the blood thinners would have only made the impact of the dissection worse. So they performed the aortic dissection surgery, which was considered successful. But because of the stroke, she was essentially brain dead.

“The Art of Resilience”

The loss of Caroline hit hard. For Mike, the grief was compounded when just a week before his mother’s funeral, his five year relationship ended. Mike attempted to process what had happened and figure out how to bear this heavy mental and emotional load. He describes this time as “devastating and surreal… I could hardly believe that my life could change so fundamentally in such a short space of time. The future that I anticipated and took for granted was snatched from beneath my nose.”

Mike reached out for support from family and friends: it felt uncomfortable when he valued self-sufficiency so much, but helped him start processing his emotions soon after his mother’s death. When he felt that he’d reached the limit of leaning on his community and the grief still felt too heavy to bear, Mike sought stories of people who had endured extreme hardship. This was when he found “The Art of Resilience” by Ross Edgely who was the first person to swim around Britain. Mike knew he had to do something big.

Edgely lays out a philosophy that resilience can be trained, like any physical muscle, by doing hard things. Mike reflects, “It was something about the pain…” that spurred him to decide on the circumnavigation. He describes Edgely’s approach: “He’s super tough, but he does it with a smile on his face, in a manner that it doesn’t deprive you of all your joy.” So in training for the circumnavigation, Mike did hard things. He started to commute to work by kayak, waking up at 4:30am to paddle 24km down the Thames from Kingston to Cadogan Pier; work a 10 hour day as a physiotherapist; and paddle back in the cold and dark, sometimes against a ripping tide, until finally making it home to sleep after 10 or 11pm.

Mike’s ‘training by commute’ lined up with the coldest time of the year; he often dealt with frost and even icicles

Putting resilience first is how Mike is approaching the circumnavigation and pinning his chances at breaking the current 40 day record. When Lambert decided to attempt the circumnavigation back in 2022, the record stood at 67 days – breaking it would be challenging, but possible. Then in 2023, endurance athlete Dougal Glaisher took a crack at it and knocked the record down to a mere 40 days. Mike thought: “This just got a whole lot harder.” Even squeezing in as much long distance training as he could, Mike knew that Dougal was the better endurance athlete. If he couldn’t match Dougal on speed, how could he make a serious attempt on the record?

The answer came back to resilience: “I can’t really compete with the fitness and endurance that Dougal has. But one of the things I can do, is can I suffer more than he did? So you know, he’s out there 10 to 12 hours. Can I be out there for 14 hours? And so if I’m out there longer, even though I may not necessarily be quicker, can I then do more distance because I’m willing to hurt more?

A visual sample of what Mike Lambert means when he says “hurt more.” All taken from training before Mike started the circumnavigation. Photos courtesy of Mike.

So far, Mike has been stymied by the weather and GPS issues to the point that he’s had to take several rest days and low-mileage days already. Having trained to push himself to his absolute limits means that Mike also knows his limits better now, and has had to make some hard choices to prioritise safety over distance when conditions got dangerous. On the other hand, Mike has already put in 4 days of more than 100km within the first 20 days of his journey. Throughout his entire 40 day circumnavigation, Dougal only completed 3 days with as much distance. If Mike wants to keep on pace, it’s looking like he’ll need some much more favourable weather and even more 100km+ days to pull off a new record. But at the end of the journey – if he’s accomplished the circumnavigation, something he feels is so unbelievably difficult as to be appropriate to recognise his mother’s early passing, Mike will be happy.

His main motivation is about his personal resilience, processing grief, and bringing awareness to aortic dissection. His mother’s early death and the traumatic experience in the hospital is what keeps driving him forward with every paddle stroke: “These types of experiences are tragically prevalent throughout the whole country. And there’s nothing I can do to bring her back. But there is something I can do so the next person, the next family, have a better opportunity.”

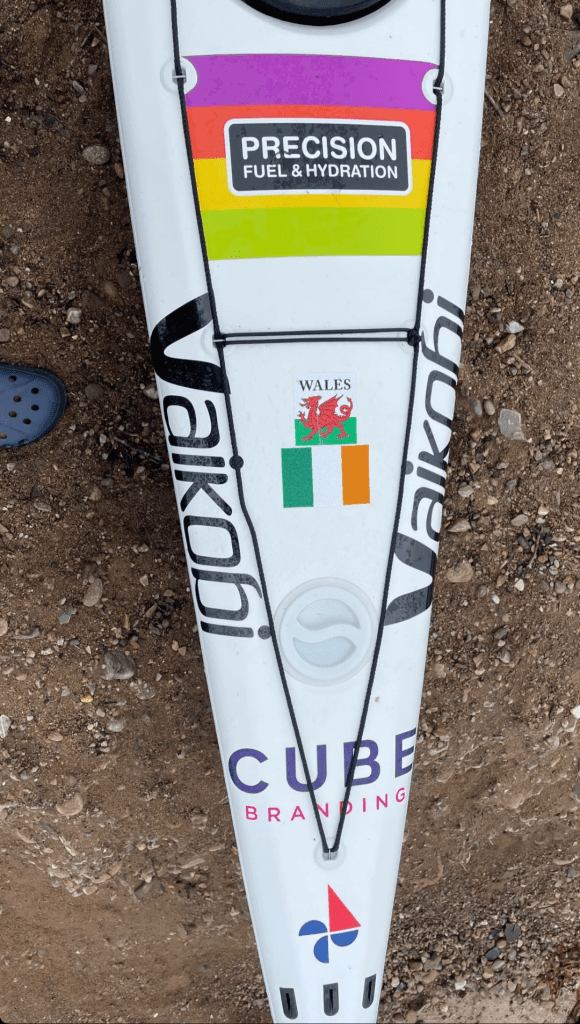

So far, Mike has raised over £14,500 for the Aortic Dissection Charitable Trust, Aortic Dissection Awareness UK & Ireland, and the RNLI who helped him out when he dislocated his shoulder at sea a few years ago (a story for another article). You can support Mike by donating to his fundraising page and following his journey online via Paddle Daily on Instagram and Facebook, Mike’s Instagram account @livelaughgraft, Strava, and his GPS tracker at livelaughgraft.com.

Leave a comment