Guest writer Dylan Kirk is longtime marathon canoe paddler from upstate New York – he’s been a fan of the UK marathon scene since setting a C2 record with Betsy Ray at the Scottish Great Glen race in 2021, and came back across the pond to attempt DW in 2023. A Friend of Paddle Daily, you may recognise Dylan from when he joined us for a late night shift on the Devizes to Westminster livestream this year. Dylan’s latest adventure was setting a new record for paddling the length of the Charles River in Massachusetts – one of the most well known rivers on the East Coast that winds through Harvard University’s campus and hosts iconic races like the Run of the Charles and Head of the Charles Regatta.

At just after 1:00AM on Sunday April 28th, Scott Ide and I became the first people to paddle the length of the Charles River in under 24 hours. Since before the arrival of European colonists, the Massachusetts, Wampanoag, and Nipmuc people have called this river Quinobequin, roughly translating to “river that turns back on itself”. Illustrating this point, Scott’s home in Framingham is within half an hour’s drive of any point along its 80 mile length. While it’s best known today for blockbuster appearances in The Departed and Good Will Hunting (Matt Damon is clearly a fan of the river), most of the Charles winds unassumingly and often unnoticed through Boston’s suburbs and exurbs.

Matt Damon looks out pensively at the Charles River during Good Will Hunting // photo: Boston Magazine

Paddling the full length of the Charles River has been gaining notoriety among local adventurers since Cameron Salvatore set the bar in 2020 with his three-day paddle from Echo Pond to the Museum of Science. Gerry Brown & Gene Hurley did this trip in about 7 days spread out over the summer of 2023. Just a few weeks before our journey on April 27th, Bill Donahue finished in two days: the new record to beat. Before 2020, the only other full river navigation we’re aware of was that of Doug Cornelius and his young children who completed the river over 10 days in 2013. Gerry, Doug, and Bill all have written beautiful accounts of their journey.

Bill started three miles downstream from Cam at a concrete chute under the village of Milford. The three miles separating Cameron and Bill’s respective starting lines consists of more mud and private property than river. Scotty and I began our journey at Archer Road, a few hundred yards downstream of Bill. While there is healthy debate about where the Charles ‘begins’, to the best of our knowledge, we are the seventh and eighth people to paddle more than 65 miles of it – at least in recent memory. It’s likely that Native Americans navigated the Quinobequin from source to sea before the colonists started building dams on it – 19 of which remained for us to portage on our adventure.

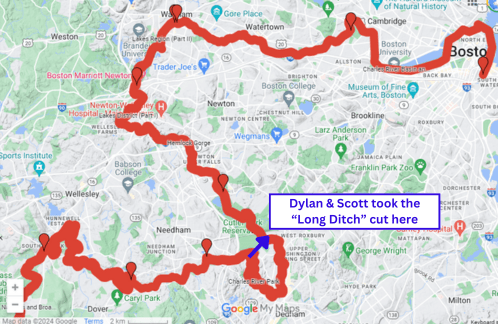

We set our canoe in the water at 5:20am in the village of Milford. As the crow flies, this is only 28 miles from where the river meets the sea in Boston. From the start to the finish by road, it would take less than an hour (traffic notwithstanding) to drive. Paddling the river meant we doubled back on ourselves repeatedly: nearly tripled, because the full distance we paddled was 72.4 miles, which we covered in 19 hours and 53 minutes. Typically with a speed record, the challenge is going fast. The challenge of the Charles River was entirely different. Immediately, we began climbing over downed trees, log jams, and overgrown brush. The early Charles is a creek: it’s so narrow, twisty, and peppered with obstacles that even experienced paddlers consider it “unnavigable”. I had hoped to keep my feet dry for as long as possible, but within minutes my neoprene boots were teeming with river water. Constantly in-and-out of the boat, we began taxing our flexibility, agility, and spatial reasoning.

Our bomb-proof Alumacraft canoe all packed and ready to go before we set off // photo: Scott Ide

Our boat of choice for the upper stretch was an Alumacraft. Scotty had taken this metal barge through the grueling 260 mile Texas Water Safari in 2021. Judging from Doug Cornelius’s account of this section, we wanted a boat we could drag over rocks without having to worry about dents or holes. We carried the canoe over most obstructions, but sometimes we’d attempt to slide over. For each log, we needed to scope out both the blockage in front of us and whatever we could see on the other side. By the time we decided to charge an obstacle, we often didn’t have room to build momentum. Some of the time, we’d get lucky and glide over smoothly. And a lot of the time… the boat would hit a log, Scotty in the bow would go up in the air, and we’d get stuck. I then had to walk forward in the boat until enough weight was on the other side of the teeter-totter, and I could kick us off the log.

One of the many, many times we were in and out of the canoe navigating obstacles in the upper section of the Quinobequin. At least the sun was up by this point. // photo: Scott Ide

I got my worst bruise early on. A white pine had fallen across the river in such a way the boat would fit under, but not with us in it. As I watched Scotty take his time going up and over the log, I imagined myself doing this much quicker and more smoothly. So I hopped up, stepped over the downed pine, and sat down. Right on a 4 inch long spike left by a broken branch. Thankfully, my neoprene did not tear, but I could tell that the spot was bloody. The wound would sting for the next 18 hours whenever it touched river water.

Continuing to the south, we portaged Box Pond Dam. It was very unclear where we should portage, but it was very clear someone did not want us there. There were POSTED signs everywhere, including one that stated “if you can read this, I can see you”. Good thing we didn’t want to hang around anyway.

On the outskirts of Bellingham the river opens up into a meandering grassy marsh. Despite the constant switchbacks, we were able to carry some speed through this area since there were no trees along the river’s edge to fall in and block us. Spirits were high with sunshine and the calls of red-winged blackbirds.

(photo: Scott Ide)

The tunnel underneath Interstate-495 had been a topic of much discussion before we embarked. Reading the river reports of those who had come before us, we knew clearance would be tight. If the water was too high, our support crew, Mike Maynard, would have to pick us up on the side of the highway. Another option was getting out of the boat and floating next to it, but of course we didn’t know what leftover construction materials or billy-goat-eating trolls might be under there with us.

As we approached a series of three box culverts, we slid off our seats and laid down in the boat. Hats came off, and we used our fingertips to gently guide the boat in a straight line. With my head cocked to the left (out of necessity), I could see sunlight on the other end of the tunnel. Partway through, presumably the highway median, the concrete deck got higher and we were able to sit up for a bit. Scotty reached into his dry bag and took a picture. Before laying back down to go under the northbound lanes, we noticed some graffiti reading “poodle ‘91”. I wonder if one of the previous Quinobequin Runners put it there. Perhaps Cameron who may have been born in ’91? Or perhaps it was an intrepid local out on the river when water levels were more conducive to painting the underside of the highway Michelangelo-style.

Laying back down again, the squeeze became even narrower than before. Scotty was getting very concerned. I wondered if we could roll to one side and swamp the boat to create more clearance. It would be especially dangerous with us tucked underneath thwarts and foot braces. Ultimately Scott came out the other side with his face barely scraping concrete. Now that this most intimidating obstacle was out of the way, the mission felt more possible than ever.

According to the Charles River Watershed Association (CRWA) and Town of Bellingham, Caryville Dam was “successfully” removed in 2016, as it had “significant hazard potential”. In his account of paddling the Charles, Bill Donahue noted that the Caryville Dam was the first dam on the Charles that has been deliberately removed: it had been the centerpiece of a thriving little village with a grist mill, cotton mill, and shoe factory until falling into disrepair by the mid-20th century. The CRWA is currently advocating for the removal of more decrepit dams along the river which should be good news for both the local ecosystems and future paddlers.

What was not “successfully” removed, however, was the chain-link fence surrounding the Caryville Dam construction site, a pipe too low for boat and paddlers, and a dozen or more hanging metal rods. After scouting the area for a good portage location, we were unable to find a way around the fence.

Dylan: I think we need to run it

Scotty: I will if I have to, but I’d like to spend more time looking for a way around.

Dylan: I’m looking forward to running it

We decided to run it.

After taking a Class II rapid as gently as you can take a Class II rapid, we came to a stop under a concrete ceiling with loose hanging rebar: the abandoned construction zone. There was a 16-inch diameter pipe in front of us, and the boat would not float underneath. We would have to get in the river, force the bow under the pipe, and push the rest of the boat through. We lowered ourselves into the river with all the grace of a Russian ballerina. Scotty spotted one piece of rebar at “scrotum level”, but we ultimately made our way through, unscathed. I breathed a sigh of relief realizing I’d narrowly missed a repeat of the ‘white pine incident’ earlier in the day. Another hundred feet down the river and we were out of the boat again, scrambling over a log.

Made it past Caryville Dam, injury-free! (photo: Scott Ide)

Sanford Mill Pond in Medway is as New England-y as it gets. An old brick mill converted into apartments overlooks a stunning waterfall. The building has a cartop boat launch upstream of the falls, and it’s here we took out to portage. We may have been trespassing on the apartment’s property, but they seemed a lot less worried about that possibility than the sign-obsessed property owners at the Box Pond Dam portage. Walking down the road with our boat to the downstream side of the dam was also a bit awkward: signage about keeping the Charles River clean made it seem like we were portaging through some kind of public conservation land, but it was vague enough that we decided not to worry about it.

“As New England-y as it gets” at Sanford Mill Pond in Medway (photo: Redfin)

At this point it was around midday, probably just past noon, and we hadn’t encountered anyone else on the river. A few more rapids and log jams later, we finally saw someone in a red Current Designs kayak paddling… upstream? As we scrambled over what was unknowingly our last cross-river fallen tree for the next 6 hours, the paddler was attempting to force his way under the obstruction from the other side. He was clearly surprised to see us. As Scotty and I climbed back into our boat, we began chatting with the kayaker about our Boston bound goal. He was impressed, and informed us Populatic Pond was just around the corner. “Have you had any other trees like this in your way?”, he asked. I looked at Scott. “Uh, at least 50”. I’d considered saying 100, but didn’t want to come off as dramatic.

Populatic Pond marked the first 20 miles, which had taken us nearly 8 hours because of all the obstructions. We were more than ready to put our paddling muscles to use, and it was perfect timing: from here, the river became wider, deeper, and faster. Our support crew, now including Scott’s wife Mary Kay Ide, met us at River Road in Norfolk for a long break. We changed clothes, applied sunscreen, scarfed a banana and some potato chips, and swapped out our trusty Alumacraft for a much lighter, much faster, Barton Bullet. The Bullet is an eighteen and a half foot Kevlar racing canoe. We knew obstructions would be far fewer from this point onward, and we could risk a faster, tippier boat. Similarly, I traded in the wooden Fox Worx for a carbon fiber GRB paddle. A deeper river meant less risk of gear failure.

Swapping over from the Alumacraft (right) to the Barton Bullet (left) at Populatic Pond (photo: Mike Maynard)

As we departed, our support crew stood on the bank answering the questions of a puzzled angler.

Mike: They’re going all the way to Boston.

Angler: That old guy!? Is that his son?

Mary Kay: The old guy is my husband.

*Scott is 55

Trying to maintain dry feet while transitioning to the Barton Bullet (photo: Mike Maynard)

The journey from Medway to Natick starts to blur in my memory. As we paddled through the hairpin turns in Millis, we were inspired to quicken our pace as members of the Fin, Fur and Feather Club practiced skeet shooting from the riverbank. As we emerged without stray gunshot wounds, the river bends straightened. Elegant estates lined the river in Dover, and I wondered aloud if the extravagant properties belonged to the Kennedys or some other Massachusetts royalty. Somewhere in this stretch is where I hit my personal low point, and it wasn’t because I’m not destined to own a massive estate on the Charles. Experience kicked in and told me to communicate this feeling to my partner but avoid negativity. We pulled over for a minute. I got to pee, eat a Clif Bar, and noticed I really hadn’t been drinking enough. 20 minutes later, I could sense my mood improving.

Natick, feeling better after I’d had a snack (photo: Mike Maynard)

The dam in South Natick was another transitional point. Taking advantage of one of the first warm spring days, anglers were out competing for fishing spots, cyclists were cruising by on the main road, and young children were playing next to the water. While much of eastern Massachusetts can be considered densely populated, the foot traffic in Natick was our first sign of the metropolis ahead.

Perhaps it was just in my head, but the river current really seemed to pick up in Natick. In what felt like no time at all, we were portaging another dam on the Needham/Dover line and putting a bow light on in preparation for twilight. Around this time Mike Maynard, our support person who’d been with us since 7am, tagged out for experienced racing paddler Stephen Miller.

Contemplating the Needham/Dover carry, photo: Mike Maynard

Following Bill Donahue’s lead, we took the “Long Ditch” above Dedham. Cameron Salvatore’s more purist run elected to go the long way around. This was the first of many drops on the urban Charles, and a notable shift to a more geoengineered river. I won’t pretend I’m not conflicted about taking the shortcut, but I do think it’s fine to run a river “as it is” and not “as it was”. The story of the Quinobequin, of the Charles, and of ALL rivers is change.

The ditch opened up to suckwater, sunset, and swans. Before long we were relying on ambient light to navigate. On our way to Newton Upper Falls we encountered our last log jam, and three good friends: Mitch & Emily who cheered from the bank, and coffee wielding Saint David who would guide us through the Wellesley portages.

From the Long Ditch to the finish we would be on the former Run of the Charles course. The RotC is Boston’s largest canoe race, and the race that got both Scotty and Stephen Miller into paddlesports. Prior to 2014, the RotC pro division would start in Dedham (part of the course the Long Ditch cut off), so Scotty, David, and Stephen are all intimately familiar with the river from here on out.

The next three portages came in quick succession. In total darkness now, we were able to find our first landing, and turn the bow light on. Less than a quarter mile later we’re out of the boat again to portage under MA Route 9. David met us here and led us through crosswalks, rose bushes, and poison ivy. After putting back in the water, Scotty and I were forced to maneuver around our very last cross-river fallen tree.

David next met us in Wellesley. From my understanding, the Wellesley portage is why the RotC became significantly shorter. Race directors at the CRWA hired local police to stop traffic at multiple intersections for portaging paddlers, and the expense became too much. After having walked this portage with Scotty and David, I finally understand what a logistical nightmare this must have been.

Downstream to Newton, the current was unreal: even though I’ve paddled this section many times, spring flooding meant conditions were higher than I was used to and at 16 hours in, I felt a rush of adrenaline. We ducked low for the golf course bridge. A USPS truck had driven into the water around here a few years ago. Some floating scaffolding signaled long overdue bridge repairs were going on underneath Interstates 90 & 95.

The Norumbega Duck Viewing Area, across from Charles River Canoe and Kayak’s Newton Boathouse is where we had our last kit change. It was 10PM, quite dark, and I was getting cold. Bob Rapant had dropped off snacks, hoping to catch us before dark. Mary Kay had picked up coffee, soup, and a chicken sandwich for me. The racing paddlers local to Boston do a Wednesday night meet up here every week, so this was not the first time I’d been stark naked in this parking lot struggling to get dry clothes on. Apparently there used to be non-paddling related reasons people ended up naked in that parking lot… but I’m only here for the paddling.

Portaging in Waltham (photo: Stephen Miller)

Mary Kay and David went home soon after our kit change, leaving Steve as our sole supporter. Before putting back on the water after Waltham’s Moody Street portage, Steve warned us of turbulent water, rocks, and a “speed bump” ahead.

“A speed bump?”

“Yeah, it’s a small low head dam. You went over one near Wellesley and probably didn’t notice.”

I’m grateful Steve phrased it this way, and I’m glad Scotty had been through this piece of river before. If I had seen this dam without his warning, I would have shat myself. The boat was moving near 10mph in the current past industrial walls designed to keep people safely OUT of the river. We were on top of the low head dam before I could really process what was happening. The river made a roaring sound, white foamy water shot up in front of us. Scotty leaned back in the bow, bracing with his paddle, and the speed bump was suddenly behind us.

To compound our fun, several turns later was the worst rapid we’d seen all day. For paddlers familiar with the upper Susquehanna, this rapid is reminiscent of 205 in Oneonta. Debris from an old dam reduced the width of the river by two-thirds for a thirty foot stretch. Water funneled to the north where a violent wave was rolling against a concrete wall. We were approaching Bemis broken dam in Newton / Watertown and for the first time that day, I was really afraid. We were so close! Would this be the end? We discussed portaging options, but as we tried to back paddle and set up a better line, the current took us. Scott often refers to Steve as Coach Miller and he lived up to the name. Steve stood on top of the downstream bridge, shouting directions over the roar of the rapid, shining his flashlight as a guideline for safe passage. We picked up speed and shot the line along the edge of the rapids. It wasn’t smooth, but we didn’t flip. Both of us got pretty wet. With temperatures in the 50s F (10-15 C), the rest of my night was cold.

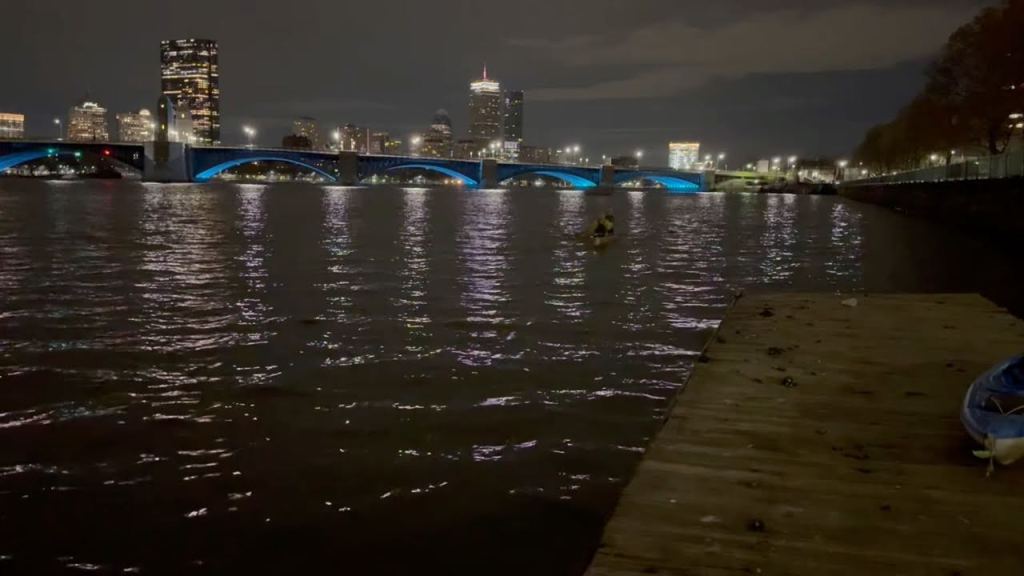

At last we completed our final portage in Watertown. Will Hunting’s bench wasn’t far now. We passed Harvard, Boston University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and all their rowing shells sitting abandoned at midnight. We passed Fenway Park, where the Sox had whooped the Cubs earlier in the day. The river was eerily quiet. A handful of lonely pedestrians were startled by my hup as we paddled under Boston’s iconic bridges. Only 364.4 Smoots to the finish.

Longfellow Bridge and city lights behind us as we approached the finish line (photo: Stephen Miller)

Steve was waiting on a dock near the Museum of Science. Our bow light had died 20 minutes before, and a small yacht was maneuvering next to its marina. No cheers, no fanfare, no timing official. It was time to rest and alert our loved ones that we had made it. We had done something special, and we had done it without race t-shirts, event insurance, or even permission.

Tips if you decide to paddle the Charles (Quinobequin)

Rapids: Class I and II rapids were periodic throughout the upper stretches. Some rapids we ran, some we walked the boat through, and some we portaged. Scott had attached NRS car straps to the front and rear thwarts making it easy to maneuver the boat when we were not in it – you could probably manage without, but these were a huge time saver and energy saver for us.

Poison ivy: I highly recommend pre-treating your skin with poison ivy wipes. The following week was rough.

Gear: Neoprene was well worth the investment. I was warm enough while we were constantly in and out of the water. In terms of our choice of craft and paddles, I felt like we made the right call starting with sturdier equipment in the obstacle-ridden upper section before swapping for lighter weight and speed when the river widened, and I think we picked the right spot to make the swap. For double-bladers, you’d probably want the kayak equivalent of an Alumacraft for the upper part of the Quinobequin, which might be a heavy-duty plastic kayak.

Support crew: There’s an African proverb that says, “If you want to go fast, go alone; but if you want to go far, go together.” But if you want to go far, relatively fast, then have a good support crew. Enormous thanks to Mike Maynard, Mary Kay Ide, Mitch, Emily, Dave Vandorp, Bob Rapant, and Steve Miller who each showed up for us to provide equipment, food, drink, clothes, coaching, photographs and yelling from the river banks. Elise and numerous others provided support in our preparation and were in touch the entire day. We also owe our success to those who shared their knowledge from making the journey previously, in particular, Bill Donahue was in contact with Scott leading up to our Quinobequin Run.

Leave a comment